Two Stage Tentacle Mechanism

Animatronics consistently took my breath away throughout my childhood–so much that I dreamed I’d be an animatronics designer one day! Years went by, and amid one-too-many high-school essays and college problem-sets later, I forgot those dreams that carried me through school in the first place.

This summer I took a few days to visit the SciPy-2016 conference with a friend. Leaving town always kicks me into daydreaming, and while we sweltered through the blaze of Austin Texas together, those animatronics dreams came back for a visit. Now, time time was ripe. I just had to build one; and this time, nothing else was there to keep me up late.

Three weeks later, a tentacle was born! Three months later, a sturdy, documented version of the build was up online for Hackaday readers.

I’ve carried this critter around to a few meetups and hacker conferences. As it’s entirely mechanically driven, it requires no batteries, no wifi connection. For the first time in my life I’ve had the joy of telling fellow onlookers “Now, you try.” And, if I’ve done my job right, I don’t need to mention just how wonderful math, science, and engineering can be. To everyone who takes those controls, they can feel it.

Build Your Own

Why keep reading about this contraption when you can have the pleasure of building your own? I’ve kept my papers in order on this build, so feel free to stop here! Take this design and adapt it for your own needs.

Credit Where it’s Well Deserved

These days, no engineering feat is done in isolation. Each of us seems to make small steps while riffing on a tune that someone else has played before. This tentacle is no exception. It’s a derivative of Richard Landon’s two-stage mechanism in the Stan Winston Tutorial Series. If you’re at-all curious about these beasts, start there. While Landon briefly discusses two-stage mechanisms, there’s no walkthrough for building one. In building my own, I decided to make one for fellow curious folks. (See bottom links!)

The Reality Behind the Mantra of Creation

Since I started college, I’ve been living a mantra of free time? build something. follow through and make it awesome. I quickly learned that, for the kid with one, two, three-years of experience, no project was too simple. I always learned something I didn’t expect. Whether that “something” was my first sucker punch from electromagnetic interference or another smack from improperly assigning part tolerances, no project was “already-designed-in-my-head” and picture-perfect the first time. For me, engineering design has been almost entirely about learning to own the dignity of iteration. Hmm, that component is a bit too long; those PID constants are a bit too jittery. For the seasoned engineer, these changes are mostly superficial, and I’ve heard stories about “the design never being completely finished.” For me, though, those changes were almost always functional. Those dimensions on the next version would be the difference between version two working nicely and version one not working at all.

I’ve been engineering for just past five years now, and I’ve come a long way. I’ve learned to test those functional aspects of my design both first and in isolation without designing the entire system around an idea that doesn’t work. With that one change, I’ve had to become more patient. Yes, “I just want to see the thing work in it’s entirety,” but now I know that there’s a dignified process of getting there. That process, while slower than building it all at once (often untested) is key. It takes every option for uncertainty in the design and removes it. In the Double-E’s world, that means a working breadboarded circuit before a committed PCB. In the Mech-E’s world, it’s a simulated motion study or a laser-cut mockup of the key moving parts.

Now, six years later, I’m proud to say that, for the first time, this tentacle has been the result of that slow, dignified process of testing individual units to the point where my first fully-assembled version actually worked!

(Hmm, should’ve listened to my design professors the first time!)

Iterate Iterate Iterate

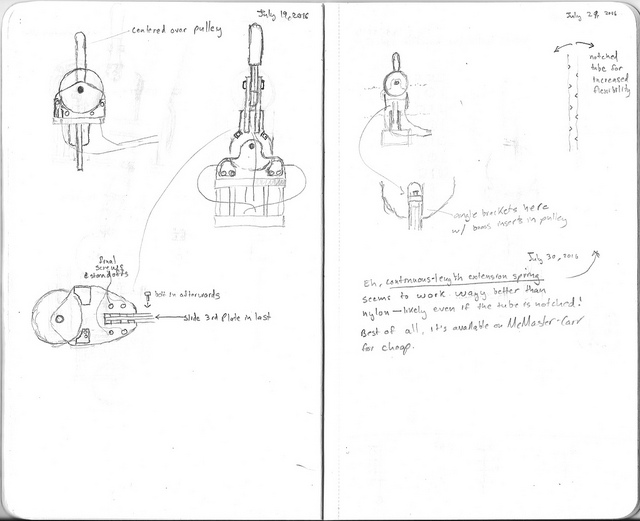

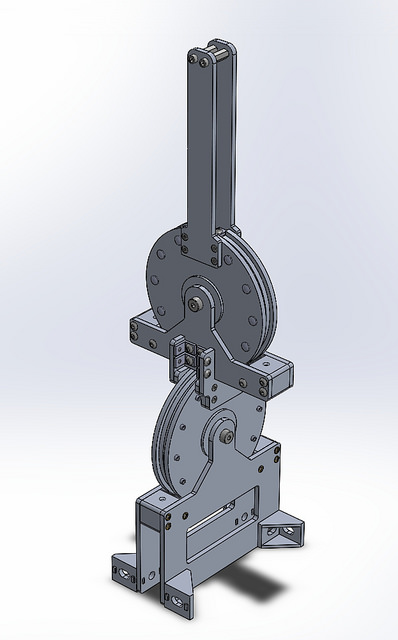

I’ve been putting lots of sincerity into making hand sketches before the CAD step. In CAD land, I’m a bit slower than the wizards of ten-years experience, so these sketches save me from abandoning or deleting models in exchange for erasing more. When I’m ready for Solidworks, these sketches give me a strong visual of the general solids that would become laser-cut plates and eventually the cable controller.

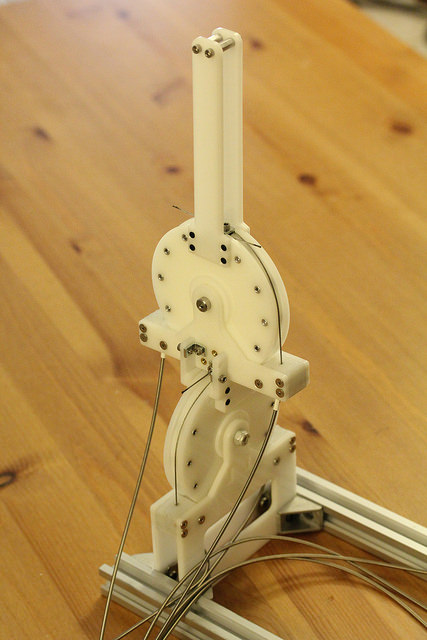

I made three versions of the tentacle, each a slightly improved version of the last. Design feels a bit like evolution, except each change is deliberate, making problems go away much more quickly with every generation.

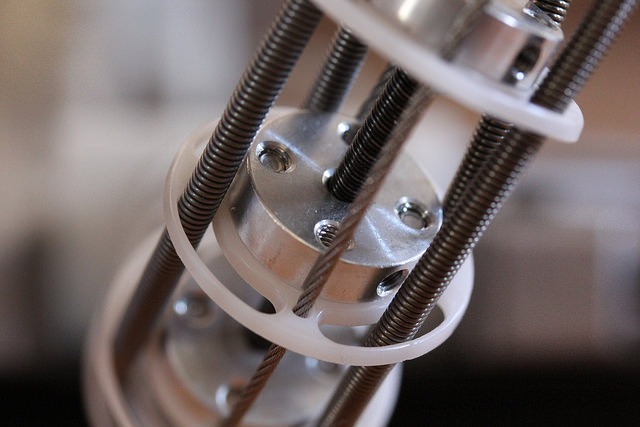

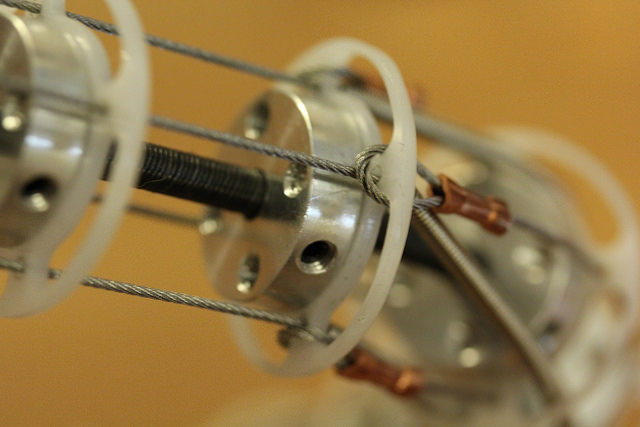

The first tentacle had a fairly thin core (speedometer cable). It worked, but the tentacle tended to twist under its own weight.

Since twist is an unwanted feature of these beasts, I replaced the (thin) speedometer cable with a thicker cable that’s made in the same way but used as flexible shaft for rotary tools. I also cut down the overall weight with thinner wire rope, thinner spring guide, and thinner laser-cut plates.

The weight loss made the overall tentacle easier to puppeteer as it didn’t tend to twist or sag under its own weight.

Putting the ol’ Laser Cutter to Good Use

At long last, this project let me flex the growing capabilities of my garage workshop. All parts in the final version were cut on my homebrew laser cutter. (The few 3D-printed parts were made with my good ol’ Form 1+.) Until now, I’ve been either borrowing time on my employer’s laser cutters or sending parts out. Laser-cutting is so fast though–often 5-minutes to parts! Having a home version dramatically speeds up the rate of iteration since no parts are left burning time in the mail. (I’m sure a few happy Glowforge owners will come to realize this very quickly.)

Extra Pics and More

- The Flickr Build Log

- Previously on Hackaday: The Bootup Guide to Homebrew Two-Stage Tentacle Mechanisms Part I

- Previously on Hackaday: The Bootup Guide to Homebrew Two-Stage Tentacle Mechanisms Part II: The Cable Controller

- Previously on Hackaday The Bootup Guide to Homebrew Two-Stage Tentacle Mechanisms Part III: Building Instructions