Much of this writeup is founded on thoughts and words shared by Prof Neil Gershenfeld at MIT Media Labs. I owe him a sincere thanks in helping me grapple with the idea of “how to make things.”

Despite spending most of my free time “making things,” I keep asking myself the questions: how do I make things? How do I get better at making these things? Fortunately, scientists, philosophers, and engineers much smarter than me have inadvertently been asking and answering these questions for hundreds of years. (For more on that, check out Prof Gershenfeld’s talk on Digital Reality.) The answer is digital.

When I first think of digital, I think: binary. Zeros and ones. By assigning enough rules (Boolean Logic) to the world of interaction between these zeros and ones, complex machines can be designed and (these days) built. Digital Computers are a fantastic example of the success of digital, but digital is much more than just zeros and ones.

Digital is a principle.

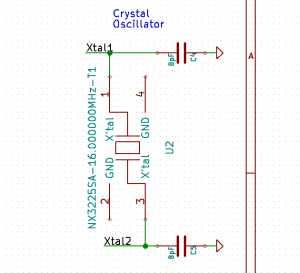

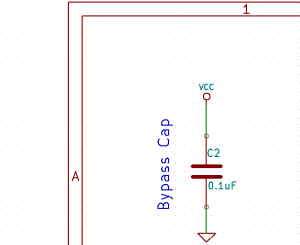

If we revisit the idea behind a computer’s architecture, we have a structure built on top of rules that live in a boolean-logic based world. Logic gates give us a way of performing decision-making (output) based on a number of binary inputs. In reality, this architecture is encoded on top of voltage levels. We’ll say “Eh, if my voltage is above a certain threshold, let’s call that a 1,” and “Eh, if my voltage is below a certain threshold, let’s call that a 0.” Now that we have this restriction, we’ve assigned only two possible outputs to a very noisy input. The true analog voltage that gets received as input is a real number, and it’s a noisy one, too. It could be anywhere from -∞ to +∞, but we’ve assigned only two possible outputs, zero and one, to this entire range of inputs. (Aside: in real digital electronics, there’s a meta-stable range too, but it’s more tightly tied to implementation than the founding idea.) Now that we’ve encoded “what counts as a zero” and “what counts as a one” as voltages, real input signals only have two options for interpretation: zero or one. The consequences of this design choice are monumental. Given this noisy, analog medium of analog voltages, we can guarantee a clean digital interpretation, which allows us to design with boolean logic, rather than dirty analog signals. If we follow the rules, we get a structured world of only zeros and ones.

Digital exists far beyond computers though. In a nutshell, digital is a manner of encoding structure on top of an inherently analog medium. By doing so, designing complex systems (machines, buildings, etc) becomes much easier since digital guarantees are made at the foundational level. In the example above, digital is both the strict imposition that an noisy input may be interpreted only one of two ways and the guarantee that a noisy output will be interpreted only one of two ways.

Let’s consider the idea of building a skyscraper. The individual construction workers can’t independently build up the skyscraper on their own. It’s not because they physically can’t do it. Even if they physically could: let’s say–even if we had a godzilla-like construction worker on our side who was easily powerful enough (and had enough hands) to construct the entire building on his own will–he can’t. The construction workers (and Godzilla) can’t build up the skyscraper on their own because they lack the digital constraints inherent to the design. They need an architect to say “what goes where.” Without this head-designer to say how the shape of the building will go together, concrete might get poured, electronics might get wired, doors and windows might get installed, but everything would be in the wrong place. The building would be a chaotic mess of individual workers doing what they do very well, but in the wrong places and at the wrong times. The building would be a mess.

In the case of the construction workers, the actual construction tasks (laying the concrete, wiring the lights, etc) are analog, but the design is digital. Digital imposes the rules as to what should go where. A concrete foundation should be laid out on the foundation, not all over the windows and splattered on the ceilings. Electrical wires should go between the walls, not in the dirt, and not in the plumbing pipes.

In essence, we’ve assigned rules to “what goes where,” and these rules are the digital principles. If we follow the principles, then, functional components on the building go, more-or-less, in the right place.

Digital exists in the plumbing of the building as a separate example in itself! Plumbing, in one sense, is just fluids moving through pipes to the the right places. This is the range of design that Analog affords us. If we allow water to flow under random pressures to random places, however, perhaps faucets on the top floor just might not work from too little pressure, or toilets might constantly gush water out instead of flushing water elsewhere. The toilet, the faucet, and the water pressure are all components that digitize the idea of fluids just “flowing wherever they want” through the pipes.

Now that we have a grasp on what digital means, we can start to understanding on how digital makes us better at “making things.” With digital, we receive principles. In the mechanical world, we have mechanisms as the underlying principles from which complex moving vehicles can be created. In the computer-science world, we have data structures, from which we can organize our decision-making process (the algorithm). (It turns out that algorithms are also digital in that they have many common founding principles for decision-making too.) In digital electronics, we have our agreement that analog voltages should only exceed thresholds such that they are interpreted as digital information, rather than analog signals.

Without digital, design becomes much more difficult. If I’m laser-cutting sheets of plastic to assemble them together for a single purpose, I can laser-cut all I want, but if I don’t start adding mechanisms and properties (joints, links, slip-fits, press-fits) to my parts, I’m assembling mush. If I’m writing software, I can type gibberish into a text editor (and get it to compile!) as much as I want, but unless, I use common principles (saving values to variables, iterating through data with loops, recursing, using trees and hash tables) my code won’t do anything useful. Digital Design not only constrains us, but also enables us by giving us a structure.

So how do we get better at “making things?” If we can understand the digital principles that compose our world; if we design under the constraints of well-known principles (and open our eyes to creating new ones), we can design at a higher level of accuracy to create things that work.

After that, it’s all just practice.